Blog #1: The importance of the accurate and honest representation and interpretation of data

Hello, world!

I’ve been thinking about starting a blog for a while now. At first, my blog aspirations were really about exploring science, talking about modern scientific advancements, highlighting role models in STEM, and developing my scientific communication skills. One day I’ll write about cool and exciting science things. BUT NOT TODAY THO (this was reference to an old Cardi B video that I quote at least twice a week, in case you didn’t catch it).

Today, for my first blog post, I want to talk about data, in general. If you’re a scientist, you probably have a love/hate relationship with data (at least, I do), and you understand the complexities of data analysis, and the ethical responsibility you have to accurately represent your data and communicate it effectively. And, because of this, when you come across data represented in media, you may look at it with a skeptical eye. If you’re not a scientist and don’t collect data in your day-to-day life, it’s likely you come across data/information from your news outlets of choice and/or social media. Both, in my opinion, are absolutely valid ways to stay informed, as long as you understand the data you’re seeing. How it was collected. How it was processed or analyzed. And how it was presented.

As a grad student, I spend a lot of my time with data, collecting it, analyzing it, trying to make it look presentable, hoping and praying it will reflect the hypothesis I have and tell the story I want it to tell (most times, it doesn’t lol). Scientific writing, and science in general, really is a form of storytelling. We have a problem, an unknown. We design a way to solve that problem and find that unknown. We tell the world what we observed, how we interpret those observations, how we could’ve done better, and what we’ll do next time. The quality of your story, arguably, is directly related to the quality of your data. Strong, significant, convincing data = good story.

An eternal ethical dilemma in science is how to report your data. Because, if you didn’t know, there are many cases where you can turn really shitty data into really, really ridiculously good looking data by applying a simple transform or normalization factor to your data, or maybe just fudging that outcome measure by a factor of 10. Who would be able to tell the difference?! (I WOULD BE ABLE TO. DO NOT DO THAT.) Ethically, it’s wrong. But it’s tempting to show your data in a way that will make the story you are trying to tell a convincing one.

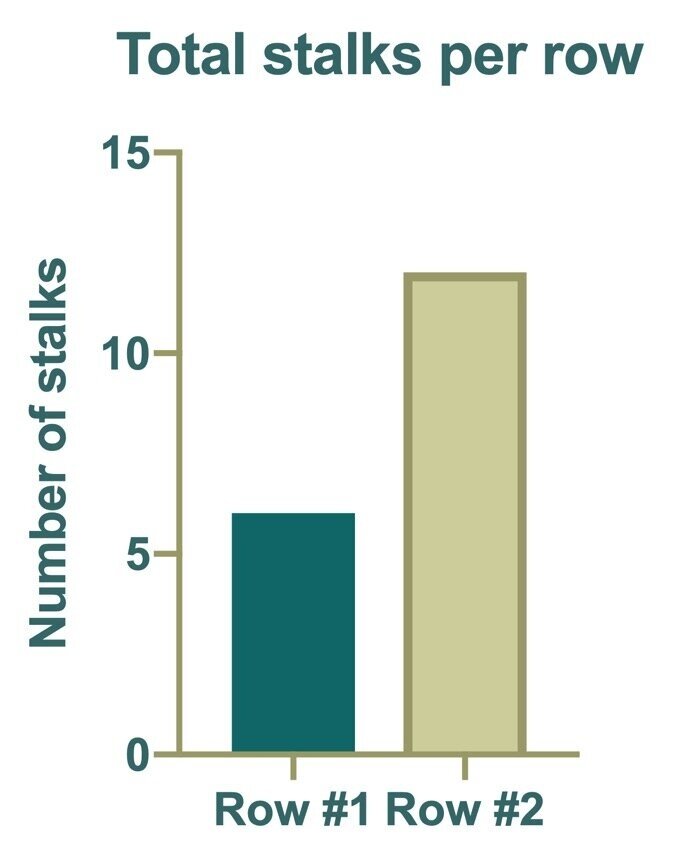

I’ll show you what I mean, by taking an example from my life. My brother recently started planting vegetables on a small garden/farm/dirt rectangle in our backyard. I helped him by planting one row of corn. He planted a second row of corn, right next to it. The seeds in these rows were randomly selected from the same envelope of seeds and can be thought of as identical. Each row gets equal amounts of sunlight and water daily. The only difference (variable) between the two rows, is who planted them. I predict that the corn in Row #1 will grow better than the corn in Row #2, because I’m better than him in most other aspects of life, so why not farming, too? The stalks just sprouted two days ago, so this is not real data, but let’s say hypothetically I collected the data and this is what I report:

Height (ft) of the tallest stalk in each row.

Row #1 had the tallest stalk, so my row of corn is better, so I’m the better farmer. I mean, it’s exactly what I hypothesized. I have a personal motive to want the better farmer (the motive = bragging rights). It makes a good story (for me, anyway). So I just accept this for what it is, right?

Hopefully you said “no you dummy lemme see the RAW DATA”

Okay, fine, here’s a more comprehensive overview of the data we “collected”:

Total corn stalks (left) and total ears of corn (right) in each row.

The height of each individual stalk is shown as a data point, horizontal bars represent the average (+/- SD) height in each row.

The number of ears of corn on each stalk are shown as data points for each row. The horizontal bar represents the average (+/- 1 SD) in each row.

When presenting my data, at first, I chose to only show that my row had the tallest corn stalk. Which is true. However, it’s not an honest representation of the full sample. I chose to represent the data this way because that is what fits my story better. However, when we look at the height of all the stalks in each row, we see that, actually, the stalks in Row #2 were higher, on average. And although the ears per stalk are pretty comparable across the two rows, brother’s row had twice as many stalks as mine did, and produced nearly double the amount of corn. So, who really has the greener thumb? (*please keep in mind this is a hypothetical. I’m not in any way admitting my brother is better than me at planting corn. And I never will.)

It’s all about perspective. And as the communicator, I gave you the perspective (i.e. represented the data in a way) that fit my story best.

Now to a non-hypothetical, real world example about what’s going on in today’s world. The #BlackLivesMatter movement is bringing much needed attention to the issue of police brutality against Black Americans in this country. A recent study described here by Vox showed this graph (below). In this article, the context of this figure is to demonstrate that the absolute number of killings of White and Black Americans have been trending slightly downwards in recent years. This figure is telling a story that, for White, Black, Asian, and Native Americans, the total number of police killings was declining (slightly) during the last decade.

If you forget the context or purpose or story behind this figure, which again is meant to show trends of police killings by race over the last decade or so, you may notice that it also shows a higher number of police killings of white Americans, compared to any other race, is consistently shown each year between 2013 and 2019. And, taken out of context, is a prime example of the “proof” needed to keep the #AllLivesMatter train rolling. More White people are killed by police each year than Black people. Why aren’t we protesting that!?

If you actually READ the article (i.e. not just look at the figure), the authors take this dataset one crucial step further: “But controlling for population (that is, looking at killings per million people) shows that it is [B]lack Americans who are most likely to be killed by police officers – that they are nearly twice as likely to be killed as a Latinx person and nearly three times more likely to be killed than a white person.” BTW - the author of the Vox article also show other figures in this article that support this fact as well, including a “synthetic cohort” study from PNAS which showed that black men in particular have the highest risk of being killed by the police in the United States; I would recommend checking it out, it’s worth the read! I’m just picking on this figure as an example.

So what happened was, this figure reports the raw data, i.e. the total number of people in each race killed by cops, without providing the perspective of the size of the population. The population of White Americans is greater than that of Black Americans. So, if we’re looking for the probability or chance that a person of a certain race will die by police fatality, we should normalize the total number by the total population of that race. [Sort of like when we want to see the probability of a coin landing on heads after one flip: 1/2; the sole outcome of heads after one flip = 1, which is normalized by the total “population”, or 2 possible sides of the coin.] When we normalize to put the data into the perspective of probability, we see that Black Americans are more likely to be victims of police fatalities than their white counterparts. In other words, the fraction of Black Americans die by police violence is greater than the fraction of White Americans that die by police violence. THIS should be the real story of the data, as this is the entire point of the #BLM movement! But this is not the story the graph was designed to tell.

A major concern is that this figure can be used for mis-representing the situation, to tell a story (or, parts of it) from a biased perspective, and in turn incorrectly informing masses of people. Imagine if (for whatever godforsaken reason) you were on the fence regarding the #BLM movement. If you saw this figure, in the wrong context, it could convince you that the movement is pointless, has no concrete foundation to stand on, when it reality it is one of (if not THE) most important movements of this generation.

And this figure is not the only one! Many, many plots and graphs shown on the news/on your timeline may have these same inaccuracies, that lead to bias in reporting the full perspective of the story.

So, in this time of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, as we see more and more racial based police violence statistics discussed on the news/social media AND this time of COVID and learning more about the virus that has caused this pandemic, I want you to question what you see, and I want you to ask the same of your families and friends. Where did this graph come from? Who collected this data, and how? What does it show me? What back-story is this figure trying to support or refute (keep in mind, we can manipulate data to tell the story we want to tell, which is very dangerous in the wrong hands). Do they cite their sources? If so, check the source – it will tell you more information about data collection/processing/analysis! If they don’t cite the source, it might not be a reliable graphic. Don’t accept everything at face value! Just because it’s a nice graph that was shared by someone your trust doesn’t mean it is the whole truth, the entire story. Always be skeptical!

The point I’m trying to make is: yes, it is the scientist/author’s responsibility to honestly and accurately report their findings; but it is also the reader’s responsibility to question what they are seeing, as it could be taken out of context or just a part of a much bigger story.

Anyway, I hope this was helpful to the 2 of you who have read this far without closing your browser to open Instagram or Twitter or something more interesting than a nerd talking about data representation (thanks, mom and dad). I’m looking forward to maybe writing another blog someday about something more happy and exciting like neuronal migration during early brain development or something!!!! Or maybe I’ll just be a one-hit-wonder on this thing, who knows?

Thanks for reading!

Stay safe out there!

-s